Women at the Front During WWI

Let’s talk technology, shall we? I’m not talking about ‘recent’ technology, like the ability to use WhatsApp, TikTok, or even Facebook. I’m not thinking about satellite radio, television, or even CD players. I’m talking about the telephone – not the cell phones that are ubiquitous these days. No, I’m talking about the plain old landline.

Honestly, does anyone even have one of those anymore?

During World War I, a telephone was cutting edge technology – especially when it came to communicating between officers and troops that were spread out over the European front. At the time, radio existed, but it could only be used to transmit Morse code. Furthermore, the radios were so heavy that transportation was a major issue. The solution? Bringing in linemen to run telephone wires throughout the front, extending for hundreds of miles.

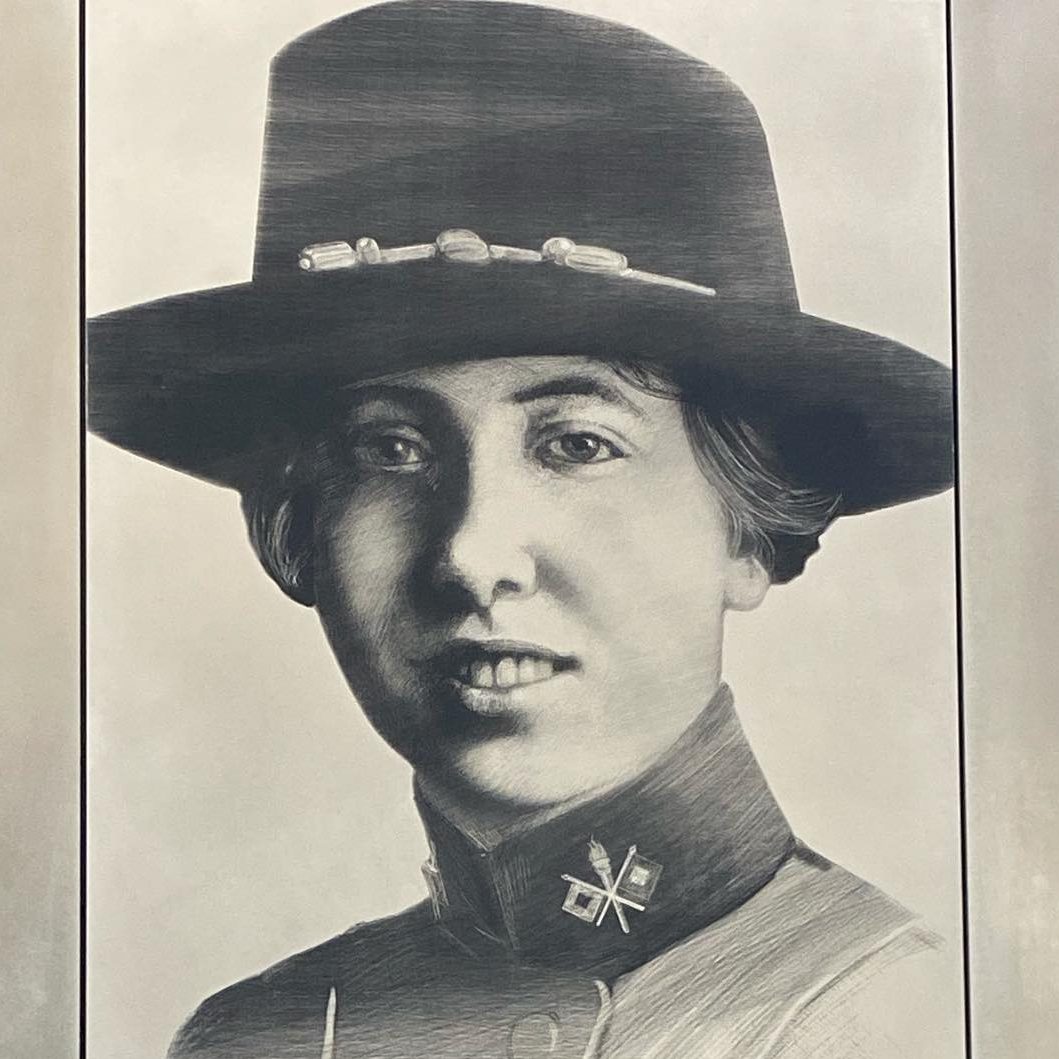

There is a backstory here about how small the Army Signal Corps was on the day the United States entered World War I. It takes an awful lot of manpower to lay the telephone cables necessary to wage a war. But that’s a story for another day. This story – THIS STORY – is the story of The Hello Girls, the women who were recruited “into” the Army Signal Corps to help serve their country.

Notice that I put “into” in quotes. That’s going to become relevant here in a minute.

At the time, the majority of telephone operators in the United States were women. In her history of The Hello Girls, Elizabeth Cobbs (2017: Harvard University Press) noted that these operators back at home were “diligent and quick, the best of them efficiently manipulat[ing] cords and plugs while fielding requests for the time and other information.”

Photo by Mary Hallock Morris (July 24, 2021)

According to the U.S. Army Signal Museum:

During WWI, General “Black Jack” Pershing advertised in all the major newspapers in America the need for female telephone operators. These telephone operators must meet certain criteria. They needed to speak French, have a college degree and be single. Over 7,000 women applied and 450 were selected. The women were recruited from the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T). The women received military and Signal Corps training. They trained in basic military radio procedures at Camp Franklin Maryland (now Fort Meade). After training, the women purchased their Army regulation uniform complete with “U.S.” crests, Signal Corps crests, and “dog tags.” Arm patches designating positions were issued. In the spring of 1918, the first thirty-three operators were on their way to Europe. They were issued gas masks and steel helmets. The operators voices were a welcome sound to the men who used the Signal Corps telephone system.

The Women in the Army website adds that “The Army Signal Corps women traveled and lived under Army orders from the date of their acceptance until their termination from service. Their travel orders and per diem allowance orders read ‘same as Army nurses in Army regulations’.”

The first 100 Hello Girls arrived before most of the American troops landed in Europe. And, they were there during the thick of the battle. A story from Cobbs’ book illustrates how tough and persistent these Hello Girls were:

Choking smoke poured into the switchboard room, where Berthe Hunt and the others were working. Shouts rang out above the quiet voices coming over the wires. “Of course we sat at the board & operated— there was nothing else we could do,” Hunt wrote. “We knew our things were going.” But they also knew they could not break contact with embattled frontline troops. A bucket brigade tried to save the switchboards. Colonel Behn climbed onto the roof over Berthe Hunt’s head and emptied pails of water that others handed up.

Here’s the sad part: Even though these women served their county, connecting more than 26 million calls during the war, when they came home from the war they were not considered to have been “in” the military after all. [See those quotation marks above were important!] Because of an Army ruling after the Civil War – when women had enlisted disguised as men – all Army members were required to be male.

Thus, the Hello Girls, who had worked through some serious battle conditions did not receive any of the benefits extended to veterans after the war. Writes Cobbs: “The U.S. government denied them bonuses, Victory Medals, honorable discharges, and a flag on their coffins.”

Speaking of persistence: These women continued to petition the various U.S. presidents for decades to gain recognition as veterans. After all, that wasn’t really outlandish, seeing how the Navy used female yeomen during the same war. In 1977, during the Carter administration, these “girls” were finally recognized as military members.

Next Time: The Radium Girls

Source

Cobbs, E. (2017). The Hello Girls: America’s First Women Soldiers [Kindle Android version]. Harvard University Press.

Other Useful Websites

June 11, 2021: Over 200 Years of Service: The History of Women in the U.S. Military

November 9, 2018: 100 Years On, The ‘Hello Girls’ Are Recognized for World War I Heroics

September 29, 1918: Brave Girl Soldiers of the Switchboard, The Sun

PBS Documentary: The Hello Girls

Library of Congress: Topics in Chronicling America (Hello Girls)

File Under

Tags